A Policy Framework for Effective Immunization Coverage of the Indian Population

Despite the widespread availability of safe and effective vaccines, disease outbreaks and deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases continue to occur due to poor coverage at all ages, especially in times of COVID-19. Immunization is the most cost-effective way that prevents suffering through sickness, disability and death. India has made significant progress on sustainable and inclusive growth in the past three decades. There is now a greater sense of awareness and expectations from the citizens as the country makes further social and economic progress. But still, there exist significant inequities in vaccination coverage across states based on various factors related to the individual (gender, birth order), family (area of residence, wealth, and parental education), demography structure (religion, caste) and community (access to health care, community literacy level) characteristics.

Reasons for Low Immunization Coverage

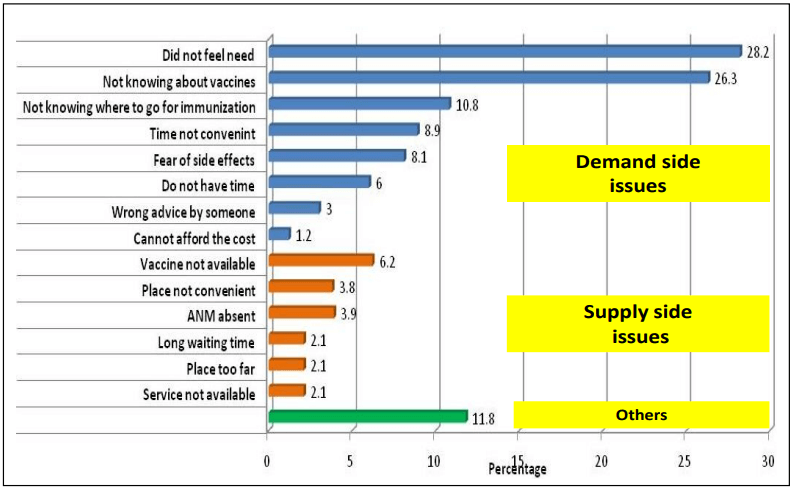

Due to multiple reasons, overall immunization coverage levels are low in India. According to the National Coverage Evaluation Survey of 2009, the reasons for low immunization coverage pertain to issues on the demand and supply side (as given in the figure below). Formative research carried out in 2015 in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Tamil Nadu showed that parents lacked awareness and did not understand the role of immunization in preventing diseases. The perceived threat of vaccine-preventable diseases was overall low. Lack of knowledge of the immunization schedule (the what, when and why), lack of urgency, and prioritization of vaccination are responsible for the low service demand.

Figure 1: Reasons for low immunization coverage in India (Source: UNICEF CES 2009)

Figure 1: Reasons for low immunization coverage in India (Source: UNICEF CES 2009)Addressing Immunization Coverage Gaps

In remote areas

- Planning predictable outreach services

- Leveraging new innovations in supply chain and mapping technology

- Conducting multi-sectoral engagement to address transport challenges

- Designing appropriate service delivery

In urban areas

- Mapping the urban unimmunized and their numbers

- Overcoming legal obstacles

- Deciding fixed service delivery schedules

- Align and coordinate between overlapping governance systems

- Use of innovative data to better account for urban mobility

- Engage strategically with private health care providers

- Develop and expand mechanisms for registration and reminders, including harnessing the potential of new technology and mobile systems.

In conflict-affected/insecure areas

- Engaging With non-traditional partners

- Security assessments

- Close community engagement

- Coordination with other humanitarian relief activities

- Flexibility around vaccine scheduling and dosing options

Promoting fixed-day, fixed time, and fixed-site strategies is effective in delivering immunisation services to ensure that communities are aware of the immunisation day. Anganwadi centres, schools, panchayat grounds and dispensaries can better serve as immunisation sites. Specific days can be fixed for each month as Village Health and Nutrition Days to maximise the opportunity for community mobilisation and service delivery.

Encouraging catch-up campaigns for all interrupted vaccine schedules (adolescent, college, travel, adults and the elderly), is the need of the hour. Similarly, intensified campaigns for boosting coverage in low performing areas and vulnerable populations need to be implemented. This will be beneficial in increasing demand and building vaccine confidence through communication strategy and stress on preventive health care than curative to prevent the spread of diseases, especially COVID these days.

Immunisation sessions may be held with flexible timings. Their reach can be expanded through mobile sessions and mobilisation by other departments. An online portal can be used for timely reporting and supervision. Performance incentives for achievement in immunisation coverage at household, panchayat, block, district and state levels can be given. Promotion of inter-sectoral synergies between organisations, communities and individuals on spreading immunisation. Strengthening collaborations with ministries, educational bodies, and NGOs need to be taken up to transform the public perceptions and attitudes and to mobilise human and available platforms for immunisation.

Continuous skill-building of health workers associated with routine immunisation programs is required to achieve and sustain quality coverage of immunisation. Training modules for front line health workers, medical officers, cold chain and vaccine supply staff need to be prepared and updated periodically to train the staff.

School health programs need to be stressed as well. The ANMs and other frontline workers’ visits to schools should be mandated at least once a year with vaccines to assess the immunisation status of children. Use of Due List by frontline health workers for tracking beneficiaries is needed and improvement of communication with parents is important to reduce dropouts, which can take place during Parent-Teacher Meetings (PTMs).

Increasing demand and reducing barriers for people to access immunisation services can be very effectively done through improved social mobility. ASHA driven mechanisms, such as the mother’s meetings, need to be utilised to promote immunisation messages, discuss how children become vulnerable to diseases, and the various risks involved with lower child immunity. It can educate them on the importance of routine immunisation. Recognising the critical role men play in immunisation decision making and uptake is important. New platforms can be created, such as father’s meetings, to sensitize and orient men on these issues as well. Community and religious male influencers need to be identified to support frontline workers in reaching out to hesitant/resistant male members.

Ensuring adequate funds for communication interventions and activities related to immunisation programs is needed. The available funds can be supplied to dispensaries or government hospitals that can be used by Anganwadi workers, ASHA workers and ANM for these communication efforts and to avoid temporary cash flow issues.

The community members, NGOs and interest groups in immunisation like women’s self-help groups should be involved in advocacy for implementation and increasing demand for services. Where-ever the reports of mistrust towards immunisation by community members are noticed, these should be studied and appropriate corrective actions need to be taken. New communication material on immunisation should be developed and disseminated widely. New audio-visual communication messages for TV and radio, along with print material needs to be developed. The government can also use social media platforms as a parallel communication channel to increase visibility with multiple target audiences. Institutions like NSS, NCC, etc., can also be mobilised to reach out to school youth and eligible children in hard-to-reach population areas to spread awareness.

High quality and timely immunisation data are vital for immunisation tracking to make informed decisions at local, national, and global levels about better reach. The introduction of new vaccines, documenting and monitoring the impact, and improving the immunisation systems performance by prioritising resources and activities should be of utmost importance. The use of technology for tracking the beneficiaries is extremely helpful. Application-based records, instead of or along with the immunisation cards will help in tracking the number of children, females and other age group people vaccinated at a given point in time. The data will be sent directly to the Department/ ministry that can track the progress and form reports to address the lagging issues and areas. This also solves frontline workers’ issues as their performance will be tracked alongside.

Vaccination Tracking System should be used to help reduce the gap between reported and evaluated coverage of vaccines. It has to be designed to collate information of all pregnant women and infants into a central database and the database will enable functions like data analysis, report generation, and thus, will contribute to better decision-making and timely and effective allocation of resources. It will act as a feedback system for health workers like nurses, midwives, ASHAs, etc., and will enable better health service delivery by drawing out action plans for health workers for antenatal care, prenatal care and child immunisation. Under this system, SMS alerts and phone calls can also be made to pregnant women, who are nearing the delivery date to remind them of the need to visit the health care centre for prenatal check-up and delivery, and to mothers about their child’s immunisation due dates. Audio-video counselling can also be done using the system to support immunisation activities and create awareness.

New technologies such as the Internet of Things, Artificial Intelligence, and Blockchain can be used track all products in the supply chain and gather data about each product through innovative and cost effective methods. This kind of access to data helps in ensuring proper distribution, prediction of the demand and supply levels, and reducing the cost and wastage of all limited resources.

The governments must reduce access barriers to vaccines and vaccination to recover from the negative impacts of the pandemic on routine vaccination coverage. Vaccine delivery channels can be expanded to include pharmacy-based, community-based, employer-based, residential-care-based, and school-based delivery of vaccinations, to support successful implementation of life-course immunisation.

A ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach is no longer appropriate in this changing world. The diverse dynamics must be addressed at sub-national levels to achieve better immunisation coverage. Immunisation programmes require continued nurturing and attention to remain as a resilient service delivery platform for primary health care and to take advantage of and harness new technologies to reach unimmunised children in the remotest parts of the country.

Subscribe to The Pangean

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox