COVID-19 and the Indian Labour Market

The outbreak of coronavirus has resulted in an unparalleled public health and socio-economic crisis. COVID-19 has heavily impacted the daily lives of people and has thwarted their ability to earn their livelihood. The case is no different for India. With the view of maintaining social distancing and other preventive health measures followed, work-from-home has become the new normal. However, it is important to understand that not all the segments of the labour market are able to function this way. The dual shock of the lockdown and pandemic has thus resulted in major disruptions in the labour market, and job and income losses of millions of people.

The spread of coronavirus has been rampant in India, with a steep increase in the number of cases being reported on a daily basis. Before the outbreak of COVID-19, India had already been experiencing an economic slowdown, with the growth rate in GDP declining to 3.1% in Jan-March quarter 2020. However, in the Apr-Jun quarter of the financial year 2020-21, the GDP growth rate has fallen to a negative 23.9%, the worst ever in economic history. All the crucial parameters like manufacturing, construction, trade and the hotel industry have witnessed a steep decline, registering negative growth rates as well. According to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI), India's Industrial Production (IIP) fell by 16.7% year-on-year in March 2020.

Impact on the Indian Labour Market

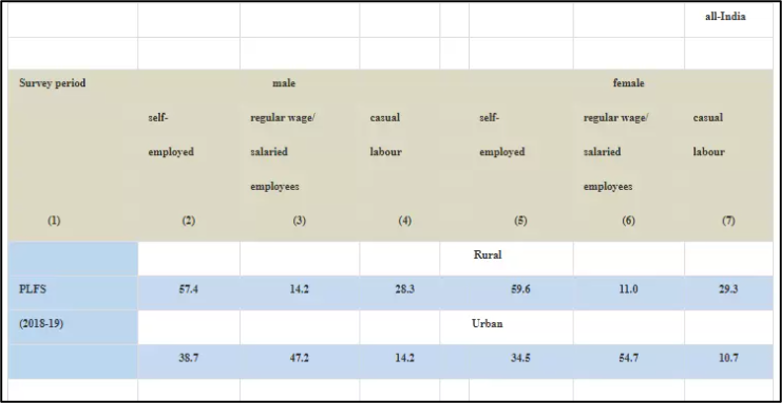

One of the worst-hit in this situation has been the labour market. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), a Mumbai-based think tank, during the period of lockdown (March-May), the unemployment rate went up from 8% to 24.3%. As of April 2020, 122 million people have suffered a job loss, with casual workers and self-employed accounting for a major proportion of this, pegging at 90 million. The effect of the shocks induced by the ongoing crisis has been particularly harsh for a specific group of people in the labour market. They can be identified as less educated individuals with low incomes who are engaged in risky and unstable working conditions. These individuals form a major portion of the informal sector. On the other hand, only a small share of the labour force is employed in salaried jobs with the perks of social security benefits. Hence, an outcome of this scenario will be a sheer rise in income inequalities. The most recent data available on the labour force is the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS 2018-19). According to the survey, the labour force participation rate in 2018-19 stands at 37.5%. The share of people self-employed, as casual labourers and as regular salaried workers in rural and urban areas can be observed in the table below:

Source: Periodic Labour Force Survey 2018-19

Source: Periodic Labour Force Survey 2018-19

Among the regular salaried workers, white-collar professionals and other employees have witnessed the biggest loss of jobs. These include software engineers, physicians, teachers, accountants, analysts and the type who are professionally qualified and are employed in some private or government organisation. According to CMIE, the employment of these professionally qualified white-collar workers fell steeply to 12.2 million during the wave of May-August 2020. This is the lowest employment of these professionals since 2016. An unprecedented 21 million salaried employees had lost their jobs by the end of August. All the gains made in their employment over the past four years were washed away during the lockdown.

Furthermore, those who are self-employed, only a minor proportion of them can be classified as employers. Of these 57.4% rural self-employed households, most of them are marginal cultivators and petty artisans, while 38.7% of self-employed households in urban areas are engaged in small shops, low-scale businesses or intermediation activities. Similarly, the casual labour households that make up almost 20% of the labour force are also extremely vulnerable and fragile in coping up with this economic downturn.

Thus, the people categorised as self-employed or as casual workers are faced with no income stability or job security and are outside the umbrella of the employment benefits offered by firms. Compared to them, the regular salaried workers do receive a salary on a periodic basis, but even then, not all of them have access to social security benefits or secure job contracts. It is thus these casual workers that are at the bottom of the hierarchy and are financially vulnerable. A sudden loss of income to these people will lead them to fall into deep poverty. The impact of the pandemic has been the worst for these sectors where the options for remote work are limited or negligible.

According to the World Bank, the shock of the pandemic is expected to push 12 million people into extreme poverty in India. Some reports have suggested that poverty in India had started rising even before the COVID-19 crisis, therefore the above estimates might even be higher. With the cloud of uncertainty looming over their heads, and the loss of jobs and incomes, the poor and the illiterate do not have the option to stay unemployed or wait for a job which serves their needs. In rural areas, we still have Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) as a fallback employment option. But such a safety net doesn’t exist for the urban labourers, who are also faced with high costs of living. The ones rendered unemployed have taken up low income and low productivity jobs, while some have migrated back to their homes.

As was expected, with the declaration of a nationwide lockdown, there was an unprecedented large-scale reverse migration of labour wherein millions of workers travelled across the state borders amidst food shortages and uncertainty about their work prospects in the future. While the government schemes ensure the availability of rations, the distribution system failed to be effective. Penniless and stranded, workers left cities for their villages on foot or bicycles, cramped in trucks and later by trains.

This inter-state migration has thus put some of India’s biggest sectors at risk. Sectors such as manufacturing, retail and wholesale trade, mining and hospitality services are heavily dependent on migrants from other states, as analysed by India Ratings and Research. “A consequence of this is a labour crunch that might hit capacity utilisation for several firms. The manufacturing sector which employs over 6 million migrant workers from other states, highest as compared to other sectors, has started suffering. The sector contributes almost 8% of the country’s GDP. Thus the manufacturing sector might face a labour shortage in the near term if labourers do not return in the coming months. This will lead to an increase in wages in the short run and a fall in profits. Another obvious impact is on the mining sector, which has been observing a decline in the past few months.

Amidst all this, many state governments have repealed labour laws. The government of the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh has cleared an ordinance that suspends all the labour laws for a period of three years with the exceptions of laws related to the abolishment of bonded labour, ex gratia payments to workers in case of work-related diseases and disabilities and timely wage payments. Similar actions have been taken by the state governments of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat with a few variations. The decision has been taken to encourage new investments, setting up of new infrastructure, and for the upliftment of existing industries and factories.

What Lies Ahead?

According to the latest estimates by CMIE, the unemployment rates have dropped to 6.4%, which is the lowest rate seen in a while, but this is hardly a cause for celebration. Other weekly labour metrics have only deteriorated, for example, the average labour participation rate fell down to 20.7% in the first three weeks of September as opposed to 40.96% in August. Similarly, the average employment rate during the first three weeks of August at 37.9% is substantially higher than the rates seen recently. But the slope is negative since the recovery is distinctly negative.

While the country recently declared ‘Unlock 5.0’, the economy is still far from being on a path of recovery. The economy is still worse off as compared to the conditions before the lockdown. The recent labour statistics only highlight the fear of India slipping from this ‘incomplete’ recovery unless the government comes up with a well-calculated recovery plan.

Subscribe to The Pangean

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox