Industrial Corridors in India: A New Vehicle for Industrialisation

According to a Briefing Paper prepared for the UK’s House of Commons, China’s share as a percentage of world manufacturing is 20% and as a percentage of its GDP, it is 27%. In contrast, for India, the corresponding figures stand dismally at 4% and 16% respectively. The Report has taken manufacturing output in 2015 as the basis, using 2005 exchange rates. The burgeoning services sector contribution to India’s GDP during the last decade has gone past 60%, whereas the contribution of manufacturing activity to GDP has remained virtually stagnant. This clearly indicates that India has been quick to adopt technological advances in the services sector, but has failed to encourage manufacturing entrepreneurship. Over the years, a clear need has been felt to boost manufacturing activity in India. Mass consumerization of Indian society due to rising disposable income and increased rural electrification have led to a rise in demand for electronic consumer goods. It is expected to reach ₹3.15 trillion in the year 2022. If quality domestic products are not available, people will buy imported goods. All this has further added to the necessity of manufacturing led industrialisation.

In order to boost domestic manufacturing, the Indian Government tried to emulate the Chinese experience as China had immensely benefited from its SEZ (Special Economic Zones) policy. On similar lines, India enacted the SEZ Act in 2005. However, Indian SEZs lacked the all-important connectivity to ports and thus, failed to augment manufacturing activity in the country. It is this realisation that has resulted in the introduction of the concept of industrial corridors that is modelled on similar corridors in Japan and China.

What is an Industrial Corridor?

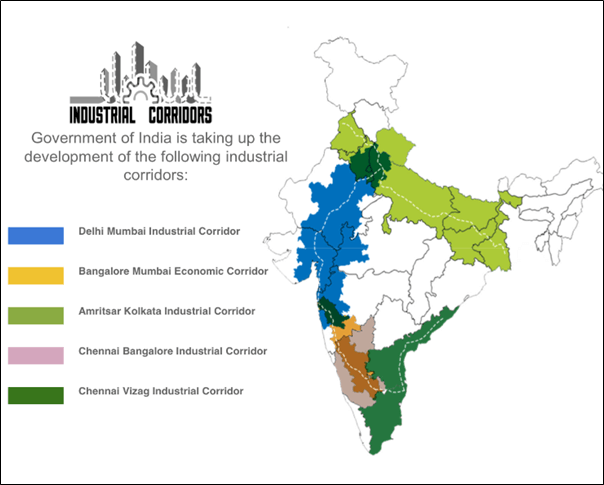

An industrial corridor or economic corridor is a pathway comprising manufacturing clusters, ancillary units and smart cities connected with rail, road, air or sea links. The Indian government has envisaged five integrated industrial corridors across the country in partnership with the respective State governments. The National Industrial Corridor Development & Implementation Trust (NICDIT) has been established as the apex body to oversee development of all industrial corridors across the country.

Industrial Corridor as Wheels of Progress

Industrial corridors recognise the interdependence of various sectors of the economy and offer effective integration between industry and infrastructure leading to overall socio-economic development. Industrial corridors lead to the creation of state-of-art infrastructure such as high-speed transportation (rail/road) networks, ports with advanced cargo handling equipment, modern airports, special economic regions/ industrial areas, logistic parks, etc. that are focused on fulfilling the requirements of the industry.

The late C.K. Prahalad, a renowned management expert, had said that over the next three decades if India does not create new cities to accommodate a whopping 500 million people desirous of urban life, every existing city would become a slum. The establishment of manufacturing zones along the industrial corridors will prevent distress migration and provide people with job opportunities close to their dwelling place. The new smart cities created will mark the beginning of a new wave of urbanisation in India and reduce pressure on existing cities.

The buzz word connecting the various programmes PM of Modi’s Government - Make in India, Digital India, and Skill India - is employment generation. Smart cities and industrial corridors are no exceptions. The educational institutions, roads, railways, airports, hospitals that will come up in these corridors is expected to generate employment and raise the overall standard of living. The government is targeting 100 million new jobs through industrial corridors.

The Way Forward

‘The wheels of progress’ are encountering a plethora of issues on their road to success, however. Of all the issues, acquisition of land at a snail’s pace is the single biggest concern owing to the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. To take an example, the $100-billion Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) was expected to be completed in three phases spread over nine years starting from January 2008. However, owing to mostly land acquisition issues, the first phase is likely to be completed by December 2019 and revised deadlines for the second phase and third phase have already been shifted to 2027 and 2037. The governments at both India’s Central and State levels need to work out a comprehensive land acquisition policy and not approach this issue in a piecemeal manner.

Secondly, as India lacks technological expertise, it is prudent to bring in foreign direct investment through established foreign entities that have the required skill. At the same time, it is also important to encourage Indian investment in setting up ancillary units in the same sector. This will provide for smooth backward integration by ensuring regular supply of raw materials and forward integration by providing ready markets. For example, the Chennai to Bengaluru defence production corridor in India’s southern States will pass through towns such as Trichy, Coimbatore, Salem and Hosur and will connect ordnance factories and defence public sector units to ancillary units (which are small and medium scale industries in the said corridor). The supplies from these units to factories and Public Sector Undertakings is an example of forward integration and purchases by the latter is backward integration.

Thirdly, in order to encourage FDI, the government needs to rationalise the tax structure. India’s corporate tax rate is high in comparison to many ASEAN countries and stands at 30%. It is 20% in Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam. Moreover, India also has very high import tariffs that make manufacturing of products with imported components economically unviable or expensive as compared to countries like Taiwan. To achieve success, the government should rationalise the tariff structure, realising that it is export promotion not import prevention that actually benefits an economy.

The strategy of industrial corridors is poised to develop a sound industrial base, characterised by excellent infrastructure and uninhibited growth of manufacturing. However, all this would remain only rhetoric if stumbling blocks are not removed and issues plaguing industrial corridor projects are not resolved. This requires a holistic approach and involvement of all the government departments, stakeholders such as farmers from whom land is to be acquired, manufacturers who would be setting units for production, transport operators, etc. With the onset of election season in India, it would be naive to assume anyone has the time to truly calibrate policy, but with a new Government and new ambitions post elections, one can only hope that the Industrial Corridors project will take on new heights.

Subscribe to The Pangean

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox