The Picture of Dorian Gray

Several years ago, in quite another place, I began work upon the largest compositional process I have ever undergone. I seemed to get it into my head as I prepared to spend a year waving my hands at the poor, unfortunate singers of St Mark’s Anglican Church, Florence, that I was far enough developed as a composer that I could write for myself an opera. Not only that, but that I could distil on my own one of the great works of Victorian literature, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray into a stage-show that would combine the sparkle of Die Fledermaus or Figaro with the grim horror of one of Britten’s darker dramas, The Turn of the Screw or perhaps Owen Wingrave. I was mistaken. It took a chance encounter with one Jamie Fox, who had had similar ideas of taking some time out in that magnificent Tuscan city, to turn my fantasy of an opera into a more cohesive reality. Over several Negroni-fuelled evenings, and many more ale-fuelled ones since our return to the UK, we translated Wilde’s effervescent and yet shockingly terror-filled novella into a two-and-a-half act show that now, slightly over three years later, has not only reached its completion, but is, even as we speak, being prepared to be brandished before the public by the wonderful people at LoveOpera.

Therefore, no small part of me is turned towards retrospection: three years ago, almost to the day of writing, I was asked by Jay Wolfe of The Wolfian to write a small article on the subject of setting about composing something of this magnitude. I did my best – I had, at that point, only just finished Dorian’s Prologue (the –and-a-half act) and had only vague ideas what the rest of the opera had in store for me. Nevertheless, I now look back upon that article and see that there is a compositional thread that stayed with me throughout the process, even from the pre-Foxian beginnings. I knew then as I know now that Wilde’s novella brought together the myriad elements of philosophy, dark humour, and gothic horror. Musically, that meant each of these strands had to be individually emphasised without any single one dominating the general effect of the music. Of course, this was no easy task. But I did find a solution, if I can really claim to have one. I studied closely how the likes of Henry Purcell, Benjamin Britten, Claude Debussy, and Richard Wagner musically synthesised various themes in their operas. I also made it a point to follow the man himself: Oscar Wilde, taking note of how he balanced these themes to create such a fine piece of art.

I feel that there is a fortunate divide between the Prologue of the work and the two Acts. It is a divide that I touched on in my previous article: much of the dialogue of the Prologue, taken from the first two chapters of Wilde’s work, consists of Basil, the painter, philosophising with his friend Lord Henry, the prime corruptive influence upon young Dorian before the boy actually arrives to kick-start the drama. This leads to moments of the Prologue that feel somewhat slower than the rest of the show, a turgid calm before a hopefully more driving roller-coaster of a storm. And I believe this is as it should be, but I may well be wrong – I shall have to see after I hear from the audiences in July and September.

However, as the previous article focussed so heavily upon the Prologue, on account of the fact that neither of the other two acts actually yet existed, I feel it may be much more suitable for us now to turn ourselves to a brief musical guided tour, as it were, through at least some of the show. Therefore, some introductions must be made:

Dorian has a main cast of six – it was quite a task to reduce down the large, high-society focused drama into six characters, but what else is a chorus for?

The characters are, in order of appearance:

Basil Hallward, (tenor) - the artist who holds Dorian as his muse, unfortunately;

Lord Henry “Harry” Wotton, (baritone) - a modern-day Mephistopheles with a heart, somewhere deep down in there;

Dorian himself, (mezzo-soprano) - I had this idea when watching Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro and realising Dorian and the teenage sex-pest Cherubino, also a trouser-role, are not so very different if you gave the latter money and immortality;

Lady Victoria Wotton, (soprano) - aside from a few witty flashes in the novella, Henry’s wife is reduced to acting off-screen, as it were. Jamie and I changed that, as you will see;

Sybil Vane, (soprano) – Poor Sybil. To fall in love with an as-yet not fully corrupted Dorian, only to so quickly jilted after one bad night on the stage;

James Vane, (bass) – Sybil’s brother arrives in the 2nd Act, and will avenge his sister… or, at least, he’ll try his utmost, raging best.

Behind these six there comes a host of minor characters that make up our show’s chorus: the society lords and ladies, the audience of a run-down theatre, the whores and opium fiends that make up the rich tapestry that is Victorian London in Oscar’s (and our) minds.

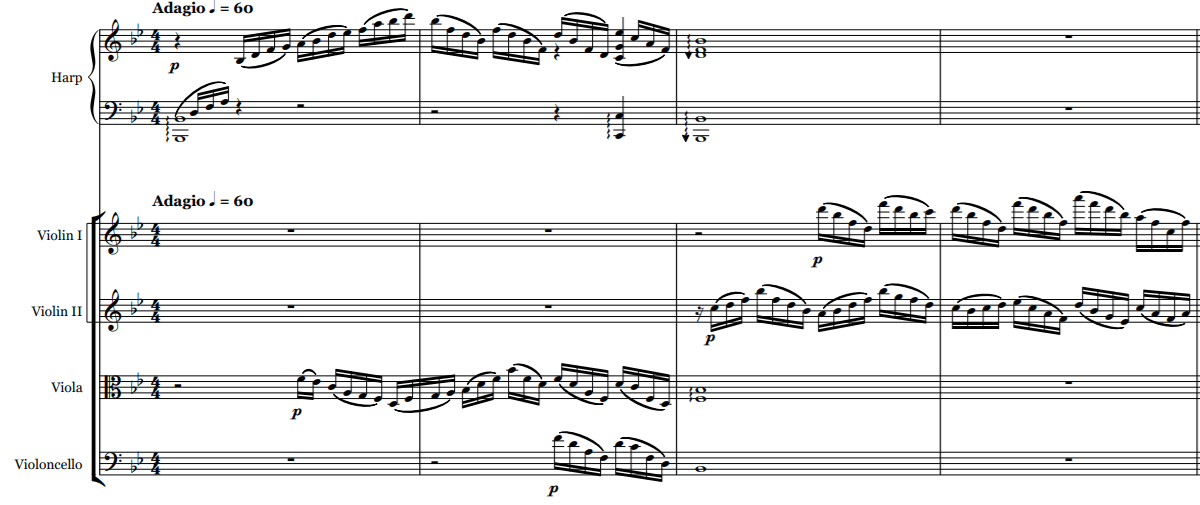

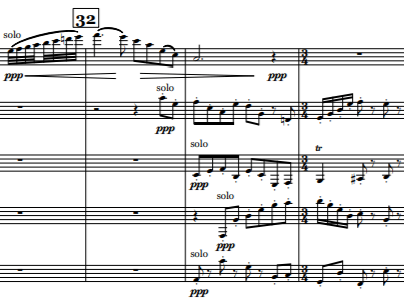

And so Act one begins, with Dorian, now in possession of Basil’s masterful portrait of him, sitting alone in Lord Henry’s living-room, awaiting his friend. It is here that I can illustrate the first influence of any of the composers mentioned in my previous article: the act opens with a harp gesture (Fig. 1) that is at once a textural back-cloth for the scene, and also acts as a leitmotif, to borrow from Richard Wagner’s vocabulary. The theme, extended by the strings and later the flute, can be said, therefore to be a genius loci – it represents the building, musically, suggesting the luxurious, lavish surroundings of the Wottons’ town-house. When, therefore, it reappears to introduce use to Dorian’s own house, in both acts one and two, it possibly tells us something about Dorian’s own following of Henry’s teachings – indeed, this ability to manipulate melodies is an incredibly useful tool, compositionally, as melodies are often indelibly linked with the emotion, location or character alongside which they first appear. Thus, the twisting of a motif by introducing it to a new context can suggest many things to an audience – watch out for it!

Figure 1

Figure 1Next, we hear Henry’s own leitmotif, languorous triplets in the horns, except this time it isn’t Henry, but his wife, whom neither we nor Dorian are expecting to see. She has some interesting things to say on the subject of Wagner, too: “I like Wagner’s music more than anyone’s. It is so loud that one can talk the whole time without other people hearing what you say!” (I must say, I hope no one uses Dorian to gossip under!) Nevertheless, as Victoria is here only for some witty repartee and to avoid her husband at this point in the drama, when Henry does finally show up she departs in short order – it’s not the healthiest of relationships.

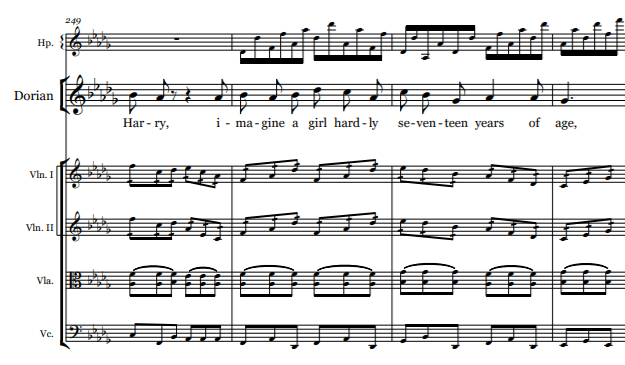

Henry’s real entrance is accompanied by a different sort of music, though. He’s a little drunk, and announces himself with a lop-sided little fanfare, before launching in a duettino of banter with Dorian, which again manipulates his own triplet motif into some fast-paced patter, as Dorian tells us that he has fallen in rapturously love with an actress, “a rather commonplace debut” as Henry puts it, named Sybil Vane. This confession leads to the first overtly romantic music of the evening, as Dorian narrates how he came across his new sweetheart in a sequence that is, structurally, a reflection of the early-Verdian style of cantabile-cabaletta, but turned entirely on its head: in Verdi, or indeed, Donizetti or Bellini, a cantabile-cabaletta consists of (as the name suggests) a slow, more relaxed section that is very ‘sing-able’ followed by a more barnstorming or pyrotechnic section. However, here Dorian sings them the wrong way ‘round: first a fast, rhythmically twisting section (Fig. 2) describing her beauty, and then two slower sections discussing first her acting ability and then how lost he is in the romance of it all (Fig. 3), before the scene peters out, and we transition to the next night, at the theatre

Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

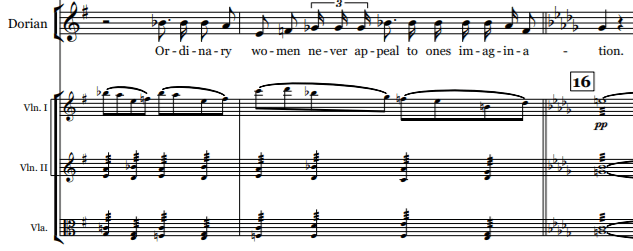

Figure 3Ah, the theatre scene. This was a lot of fun to devise – I recall Jamie gesticulating wildly as he explained to me that this was to be no great work of Shakespearean spectacle, but a farcical experience, with a wooden, nervous Juliet and a stout, middle-aged Romeo with a bit too much gut and far too much Brian Blessed. And in the midst of it all sits Dorian, trying desperately to convince Henry and Basil that Sybil is, in truth, a wonderful actress and well worth his love. Therefore, I put my comedy hat on, and have tried to construct a woeful imitation of Gilbert and Sullivan as an overture to this play-within-a-play. There is no emotional core to this moment, no attempt to tug at the heart-strings as one would expect from an overture to a performance of Romeo and Juliet. It’s just dross. As is the acting that follows it, but for that I had to get more creative.

Figure 4

Figure 4First, I set up a sense of scurrying tension within the on-stage audience by way of a tiny fragment of melody that, when repeated over and over, becomes an ostinato-texture which, much like the harp motif of Fig. 1, serves as a backdrop for the entire scene. Over this, both our trio and the on-stage audience mutter between each other until the curtain comes up and we see a sequence of three scenes from the play, each successively worse: steadily, we progress from thin, dull orchestration and bad singing, add in meandering, meaningless chromaticism and unstable harmonies, and finally top it all off with some bombastic as the crowd get steadily more unimpressed with the performance (Fig. 4).

I think I write quite good ‘bad’ music, sometimes…

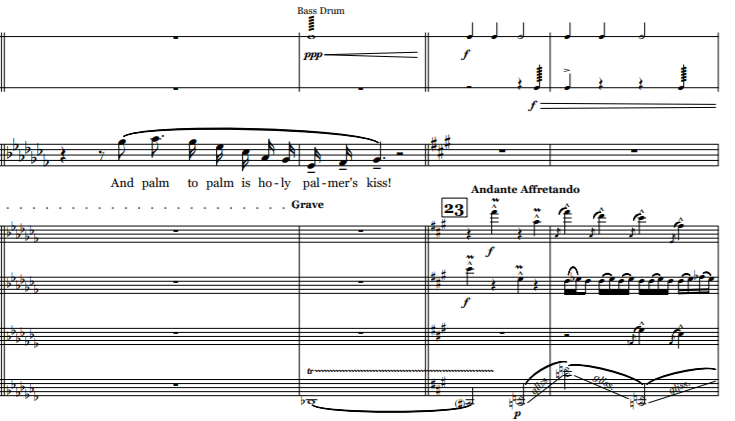

Ultimately, Basil and Henry resolve to leave before the end of the show and leave Dorian behind to talk to poor Sybil. Poor Sybil who is, in point of fact, much more vivacious in real life than she ever was on stage, and so very much in love with Dorian, as illustrated by her motif, which is itself an extension of Dorian and the portrait’s own melody (Fig. 5, showing Dorian’s melody on top, and Sybil’s extension below it), before flourishing into a much more lush romantic gesture, and finally a re-hashing of one of Dorian’s own earlier cantabile sections. She is so consumed by what could kindly be called her infatuation or, worse, obsession with Dorian that she does not create her own music, merely adopts his. And yet, in his refusal, Dorian himself mimics Henry’s own more impassioned music from the Prologue; neither of them is, in truth, free from obsessive thoughts about another person, or the ideals that they represent. Unfortunately for Sybil, Dorian’s ideals lead him to abandon her, storm out, have a wild night on the town before returning to his house, alone.

Figure 5

Figure 5To cap the act off, Jamie and I had a bit of a predicament: the novella contains a long time-skip before a certain climactic scene that we both wanted to include as the finale of Act One. Whilst this reads incredibly well on paper – as the years pass, Dorian becomes more and more corrupt until he goes beyond the pale – this does not work near so well on a stage, where the audience is best served by having a cohesive narrative, at least according to critics as far back as Aristotle and the classical unities (of action, time and place). Thus, we conflated several scenes from the book in order to make this finale to Act One as impactful as can be. As Dorian recovers from his hangover, portrayed by slow, chromatic triplet descents, his torpor is interrupted by the arrival of Basil, who has bad news. This is the first change, as Wilde has Henry come to Dorian’s house to deliver this particular news – that Sybil has committed suicide. Basil is, therefore, able to finally act more overtly and lovingly towards his muse. This also sets up a further conflation, as there are two scenes of Basil, in his moralising fashion, trying to help Dorian. In the one, he asks to see the portrait and is rebuffed, and on the other, many years later, Dorian crosses a line. Basil is never seen again.

As we conflated these three scenes into one, I introduced, musically, one last thing: the poor soprano playing Sybil would otherwise have only two scenes, and, feeling sorry for her, I wrote her voice into the scene. Dorian, so affected by the news of her death, can almost hear her calling out to him, turning a duet into a trio, and having the final action of the scene, and indeed of the first half of the Opera, become the deaths of two of Dorian’s principals (Game of Thrones style). I don’t believe I know of another opera where both the tenor and the soprano are killed before we make it half-way. That ought to make an impact – and hopefully leave the audience as eager to see the conclusion of the drama as you may well be to read the final instalment of this little-guided tour through my opera!

Subscribe to The Pangean

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox