American Psycho, Capitalism and the Hindu Gods

The morning routine scene in American Psycho is, without a doubt, ensnaring. The intricate detail with which Patrick Bateman describes the various toiletries he uses, the near-artistic manner in which he applies facemask, and the way in which he innocently cautions against using alcohol-based aftershave is hauntingly beautiful. The question is: apart from the obvious aesthetics of the scene (and Christian Bale’s perfect physique and looks), why is a bloody personal hygiene tutorial so enchanting? Is the scene so surreal that it somehow reminds us of our own reality?

American Psycho, it is acknowledged across the board, takes a dig at the hyper materialism and obsessive image-consciousness of 80’s American yuppie culture. But its relevance to today’s advanced capitalist society is unmistakable. Patrick Bateman’s obsessive beauty regimen is a mirror for the multiple ways in which we craft detailed masks to project an image that conforms to certain appearances of wealth, happiness and even ‘liberalism’. It mirrors Elon Musk’s workaholism, which seeks to portray him as a self-made man, when in fact his father was the owner of multiple emerald mines. It mirrors the life of many Instagram models whose very source of income is a self-objectification of their bodies. It mirrors Pride Month, which is nothing more than liberal hogwash, and it mirrors us, the people who check-in on Facebook when visiting an expensive restaurant or put up such perfect pictures when visiting sweaty, crowded, dirty and drug-filled music festivals.

In short, the morning routine scene in American Psycho serves as a perfect allegory for the way in which society immaculately creates the face of capitalism. In providing this allegory, it serves as a starting point for a much more profound idea: that ‘capitalism’, instead of being a mere economic system is actually an elaborate socio-psychological construct that moulds human beings in a certain way.

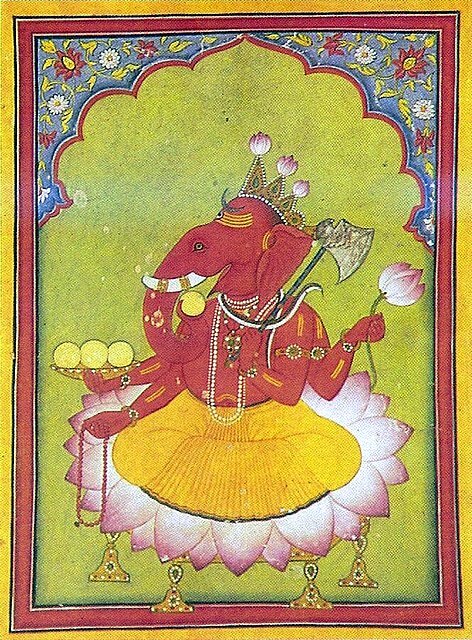

The difference between capitalism per se and an economic system merely involving private ownership of material wealth is, rather curiously, provided by the Hindu tale of Ganesha and Kubera. For those who may not be aware, Ganesha, typically portrayed with an elephant head and pot belly, is the lord of wealth in Hinduism, he is traditionally associated with all things related to business and commerce and is the favourite god of all traders and merchants. Kubera, is a yaksha, he is a ‘lesser being’ when compared to a ‘god’, but still one among the divine. Kubera is known for his fabulous wealth and rotund figure, he is known for being a great hoarder of riches and fine things, from perfumes and food to mythical flying chariots and gold.

One day, Kubera decided to host a grand feast in his opulent home to please all the gods, the intellectuals and other beings. He invited Ganesha as well. At the same time, he taunted Ganesha for living with his parents, the gods Shiva and Kali, who represent the destruction of all material reality, stating that the latter must not get well-fed in a household of literal destroyers. Ganesha accepted the invitation, and when he turned up to the feast, he ate like no other. Kubera was initially pleased to feed such an important god, but Ganesha kept on devouring the food, eating more and more and more.

After Ganesha had consumed all that was in the kitchen, he began to eat all of Kubera’s possessions: his gold, his furniture, his home, everything. Kubera ran to lord Shiva, the destroyer of the universe and Ganesha’s father, seeking help. Shiva calmly instructed Kubera to carry with him a small pot of plain rice to the lord of wealth and to offer it up in all humility. Kubera did as told, the lord of wealth was placated. After finishing his rice, the lord of wealth asked Kubera if he had finally understood the rationale behind Ganesha’s actions, Kubera confessed he had not.

Ganesha explained that Kubera was a hoarder of wealth, that he saw material pleasure not as the part and parcel of life but as the end in itself, while Ganesha was the lord of wealth, he ate not to blindly chase more food but to appreciate the goodness that good food and wealth brings. Kubera’s feast, Ganesha said, was made to honour excess, and Ganesha was only seeking to illustrate the folly of believing in excess—by showing Kubera the true meaning of consuming for the sake of consuming.

It is important to note that it is Ganesha—the child of the destroyer god—who is the lord of wealth instead of Kubera. Being the lord of wealth means one has mastery over it, and Kubera, instead of having mastery over wealth has wealth itself as his master. And this is what capitalism is: not a mastery of wealth but of service to it, of slavery to it. It is this slavery to wealth which is making us literally consume like Ganesha consuming Kubera’s vanity feast. Corporations are prepared to destroy our whole planet in order to create products for our consumption. While we do not go killing and eating people like Patrick Bateman because of our envy of another’s slightly different business card, we do, in our desire to have more and to be recognised as having more, devour goods like sharks frenzied by chum. We’re all Kuberas today, unable to understand that it is the sumptuousness of plain rice we must cherish over the newest (and-not-at-all-upgraded) iPhone.

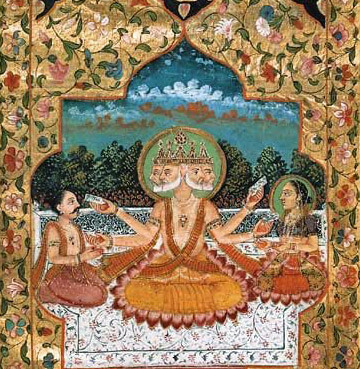

This is where the story of Brahma, the creator god of Hinduism, comes in. After Brahma created the universe, he ventured to create the first woman, once he created her, he did the most egregious thing: he fell in love with her, his own daughter. He tried to chase her wherever she went, sprouting four heads to keep an eye on her in every direction. He even sprouted a fifth head when his daughter tried to jump over him to avoid his lecherous gaze.

This story represents what capitalism does to the human mind. The act of creating the woman involves Brahma carrying out complex fire sacrifices and reciting great hymns, much like the creation of goods in an industrialised, capitalist society involves complex contractual and credit arrangements along with the furnaces of factories and the sacrifice of the millions who contribute their labour. The fire sacrifice has a yajaman, the declared officiator of the fire sacrifice, the one who must reap the benefits, in other words, the capitalist and all of society itself. Brahma’s taboo act of falling in love with his own daughter represents our love for everything capitalism has to provide. It represents our yearning to dominate and control everything by gaining full control of the material world through the means of production. Brahma’s fifth head represents our ego, our narcissistic belief in having subdued all of creation through the fire sacrifice of capitalism. It must be noted here that Kubera, i.e. the one who invited Ganesha to his feast, is a direct descendant of Brahma, very clearly implying that Brahma’s will to create and consume literally gives birth to a servitude towards wealth.

The parallels of Brahma’s lustful and forbidden act are drawn even more starkly in American Psycho. Patrick Bateman looks at himself with great admiration when he engages in that threesome with two prostitutes, much like capitalism looks at its billboards and high rises with awe. He video records himself having sex and then proceeds to inflict very serious wounds on the women as a declaration of his might, much like the capitalist overworks and abuses the labour that gives him his profits. In killing one of the prostitutes later on, he declares his will to power, much like Brahma sprouting a fifth head, illustrating the extent to which he will go to fulfill his bloodlust and hunger for the allegorical carnal pleasure.

It is after this point that the parallels between American Psycho and Brahma’s story end.* American Psycho* ends with Patrick Bateman declaring that there’s no escape even when he has confessed to his crimes. In a way, it reflects the quagmire that the Marxist accuses the Liberal of being in, i.e. that the Liberal has no way to escape capitalism even if he recognises it is bad because capitalism itself animates him so fully. To the Marxist, true escape lies in the ending of capitalism itself, it lies in ending the superstructures and narratives (like private property) that sustain our reality and justify the idiotic sum of material relations, so that we may have true common ownership of wealth. And it is here that the story of Brahma arrives again to educate us.

Once Brahma’s fifth head grows, Shiva, the destroyer god, who is usually lost in meditation awakens. He takes the most fearsome form, called Kala Bhairav (literally ‘dark frightful creature’). Kala Bhairav rides dogs, which are unclean animals according to Hindu priests, and has great talons. It is with these talons that he hacks off Brahma’s head, which he then turns it into a cup for drinking hemp. The symbolism of this act should not be lost on anybody, Shiva here is literally beheading the human ego, dramatically forcing contemplation. In converting the head into a drinking cup, he’s reminding humans of the falsehood of capitalism that leaves them lost in an unreality of their own making.

Interestingly, Shiva’s act, even if seemingly mirroring Marx’s call for the death of capitalism, is radically different from it. Marx’s dialectic materialism is, ultimately, that only, it is materialism. Marx’s philosophy, by putting economic relations or property relations as the base, stupidly puts Brahma’s fifth head as the one true thing, calling for the other four to be cut off. Marxism does not go to the very thing that drives the fire sacrifice of capitalism and the sprouting of the fifth head: the human desire to dominate material reality, the human ego which seeks to consume, create and serve wealth as an extension of itself. Shiva’s act seeks to destroy that very thing, to release the human being from his need for capitalism, to release the human being from his need to control material reality in the first place.

The moment we stop conceiving capitalism as an economic theory but rather as a psychological, social and even spiritual state of society is the moment we understand what it truly is. Capitalism is an outgrowth of our very consciousness, it is an attempt at fashioning reality itself, which places the material as paramount. It represents our need to control the world around us, to subdue the elements to do our bidding, and in the process to create goods and services that will give our lives meaning and worth. But it is in the process of creating meaning that the human ego rears itself, seeing its petty creation as all that matters, when reality is much larger than we would realise. To overcome capitalism, we must destroy it at its roots which lie deep within the human psyche, we must cut off our heads, allowing a better one to take its place.

*I owe my gratitude to Devdutt Pattanaik, Slavoj Zizek and Adi Shankara for this article, without their ideas and teachings I would not have even conceived of this article. *

Subscribe to The Pangean

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox