Of Diplomacy, Domination and the South China Sea

In his book, On China, notable American diplomat Henry Kissinger wrote, “The highest form of warfare is to attack [the enemy’s] Strategy itself; the next, to attack [his] Alliances. The next, to attack Armies”. As elaborated by Kissinger, China seems to be following the art of strategic encirclement in diplomacy’s new theatre, the South China Sea.

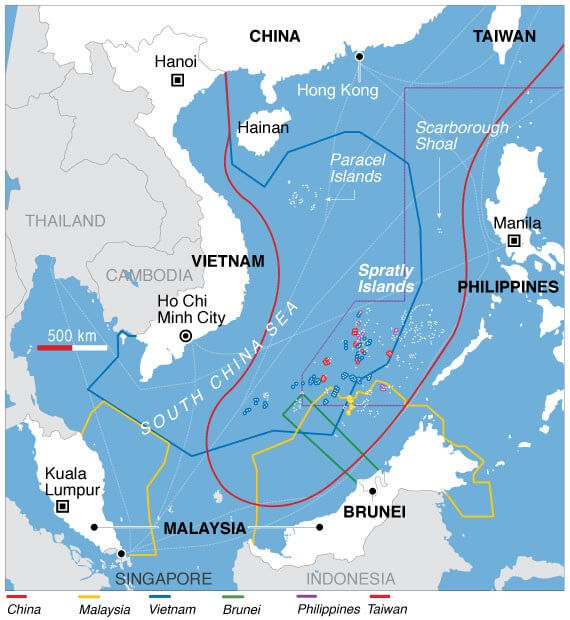

Geography

The South China Sea is a part of the Pacific Ocean, with the Strait of Taiwan in the Northeast and the Straits of Malacca in the Southwest (as shown in the map). The littoral countries of this disputed sea are China, Taiwan, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam.

The primary island chains in the South China Sea are The Paracel, the Pratas and Spratly Islands. The Scarborough Shoal, a triangle-shaped chain of reefs and rocks with a total area of 150 square kilometres, is another important geographical entity.

The Conflict

Till the end of World War II, not a single island in the South China Sea had been occupied. In 1947, China demarcated its claims over the South China Sea with a U-shaped line made up of eleven dashes, covering almost the entire area. Newer dimensions were added to the conflict following the formation of Taiwan in 1949. In 1953, the nine-dash line prevailed over the earlier eleven dashes, when China withdrew its claim over the Gulf of Tonkin. The claimed area stretches from Hainan Island, covering Paracel and Spratly Islands which comprise over 90% of the South China Sea. On diplomatic fora, China justifies its claim stating the Treaty of Tientsin with France after the Sino-French War in 1885, and the Cairo and Potsdam declarations after the defeat of Japan in World War II.

Claimants for the Paracel Islands include Taiwan, Vietnam and China. Vietnam cites 17th century, Vietnamese scholar Do Ba to justify the fact that it once actively ruled over Paracel and Spratly islands, and thus has territorial rights over them. As for the Pratas Islands, they are administered by Taiwan but claimed by China. Malaysia and Brunei also claim the territory that falls in their exclusive economic zones. While Malaysia claims some islands in Spratly, Brunei does not. Philippines, Taiwan and China claim the Scarborough Shoal, which China also calls the Huangyan Island.

Importance of the South China Sea

The South China Sea is an important trade route, supporting trade worth $5 trillion. Secondly, it is a rich source of hydrocarbons and is an abundant fishing ground. According to the United States Energy Information Agency, there are 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in deposits under the South China Sea. Its fisheries account for 10% of the global total.

The South China Sea holds strategic importance for China for two more reasons. First, China is dependent upon West Asia for its energy needs. The trade via sea has many choke points like the Straits of Malacca, Sunda Strait and Lombok Strait that have remained blocked in the past. This proved harmful for China and thus domination of the sea would be pre-emptive action to save this important route. Secondly, aggressive posturing in the South China Sea would help China enhance its domination in the Indian Ocean. This would be a countermeasure to the United States’ growing hegemony in the Indo-Pacific region.

Vietnam-China Dispute

In 1974, China and South Vietnam fought the battle for Paracel Islands. China won and took over the entire archipelago. Following the Vietnam War, North Vietnam, which earlier supported China’s claim, put forth a united front against Chinese domination. As discussed earlier, Vietnam claims the Paracel Islands and denounces the violation of Vietnam’s sovereignty by the forceful occupation of these islands. In 1988, another standoff occurred following a skirmish between Vietnamese and Chinese soldiers over the Johnson South Reef in the Spratly Islands that killed 64 Vietnamese.

The 2014 China-Vietnam Oil rig crisis heightened tensions relating to the ownership of islands in the South China Sea. On May 2, 2014, China National Offshore Oil Corporation moved its $1 billion Hai Yang Shi You 981 oil rig to a location closer to the Triton Islands, the southwestern-most island of the Paracels. The location was near Vietnam’s hydrocarbon blocks 142 and 143. Vietnam protested by sending 29 ships to disrupt the rig’s operations. The tensions at sea led to anti-China protests in Vietnam which escalated into riots. Many foreign businesses and Chinese workers were subjected to looting and vandalism. On July 15, China National Offshore Oil Corporation withdrew one month earlier than originally announced, defusing the crisis.

In July 2019, a large-scale standoff took place between the coast guard ships of China and Vietnam when a Chinese oil exploration ship entered disputed waters near the Spratly Islands. Vietnam demanded an immediate withdrawal, while China refused to do so, leading to another dispute between the nations.

China-Philippines Dispute

Until 2012, Philippines exercised de-facto control over the shoal. The 2012 Scarborough standoff was initiated when the Philippines accused Chinese fishermen of illegally collecting corals, giant clams and live sharks. Following a tense standoff wherein the Chinese vessels refused to leave the shoal, the unsuccessful bilateral negotiations forced the Philippines to back off. China gained control and drove Filipino fishermen away from Scarborough Shoal. In 2013, the Philippines took China to the Permanent Court of Arbitration, to challenge the nine-dash line that violated the Philippines’ sovereignty under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (1982). The court ruled that China had violated the Philippines’ sovereign waters as the nine-dash line included the Scarborough Shoal and the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). China outrightly rejected the ruling and refused to vacate the Scarborough Shoal, questioning the court’s ‘jurisdiction’. Philippines rejoiced this judgement as the ‘trial of the century’.

Despite the ruling of the Hague tribunal, China continues to violate the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone and engages in overfishing. On June 9, 2019, a Chinese vessel was involved in a boat ramming incident, which threatened the lives of 22 Filipino fishermen. In another incident in late July, 113 Chinese fishing vessels were spotted near the Philippine-administered Pag-asa Island in the Spratly archipelago.

Despite continuous violations, the Malacañang seems to be wanting warmer ties with its Chinese counterpart. President Duterte recently revealed that he had reached a ‘verbal agreement’ with President Xi, for allowing Chinese fishermen in the Philippines EEZ. As a part of Duterte’s bilateral visit to China in 2018, a preliminary agreement was reached for oil and gas exploration in the South China Sea. Critics smell foul play at the increasing proximity and condemn Duterte for failing to act on the Philippines’ arbitral victory. The reason for this shift is attributed to China’s economic clout and growing investments in the infrastructure sector, essential to support the Philippines’ economy.

The aspiring hegemon is proactively utilising money diplomacy to win strategic partners. According to reports, a secret deal was signed with Cambodia to allow Chinese forces to use the Ream naval base. As in the Philippines, Chinese funded soft loans and investment in Cambodian infrastructure projects have brought ‘warmth’ to the bilateral ties. Encirclement Attack is the norm being adopted by China, and how the nation’s money diplomacy further polarises the South China Sea dispute would be something to watch out for.

Subscribe to The Pangean

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox