No Longer Forgotten

Despite witnessing one of the bloodiest wars and being the only region in the world divided by the Cold War, the Korean Peninsula and its history, until recently, has failed to make its way into the mainstream. It’s only in the last 20 years that the peninsula has gained the world’s attention: the notorious Northern part has become infamous for its nuclear weapons while the South is taking over the world with its Hallyu wave.

After 36 years of the ruthless Japanese colonisation, the Korean Peninsula was liberated on August 15, 1945. It was a joyous occasion for the peninsula, for the Koreans were now independent, and the pain and humiliation of the Japanese invasion were over.

As the Second World War ended and Japan surrendered, the Korean peninsula fell into the hands of the winners of the World War, i.e. the Allied powers. While the Soviet Union spread its communist propaganda in the North, the US vouched for democracy in the South. The peninsula was divided along the 38th parallel in 1948 due to these ideological differences, forming two nations, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the North and the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the South. For the rest of the world, they might be North and South Korea, but both believe they are the only legitimate Korea. Initially, blessed with more heavy industries, the communist DPRK’s economy rose, while the South struggled.

For the next two years, North and South Korea were heavily militarised with the help of the Soviet Union and the US, respectively. While the US and the Soviet Union had been regarded as key reasons in the peninsula’s division, the military troops acted as deterrents and prevented war between the two Koreas. However, as the troops started withdrawing, it left the Koreas on their own, making the prospects of war more imminent.

In June 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea swiftly overtaking much of the country. The South Korean army was unprepared and inadequately equipped to face a sudden attack. In September, however, the UN force, led by the US, launched a counter-attack and advanced into the North. China, then, sent in troops to aid the North, shifting the balance of the war. In 1953, the fighting ended with an armistice that approximately restored the original boundaries between North and South Korea. This armistice inaugurated an official ceasefire but did not lead to a peace treaty, and so, the two are still at a cold war against each other.

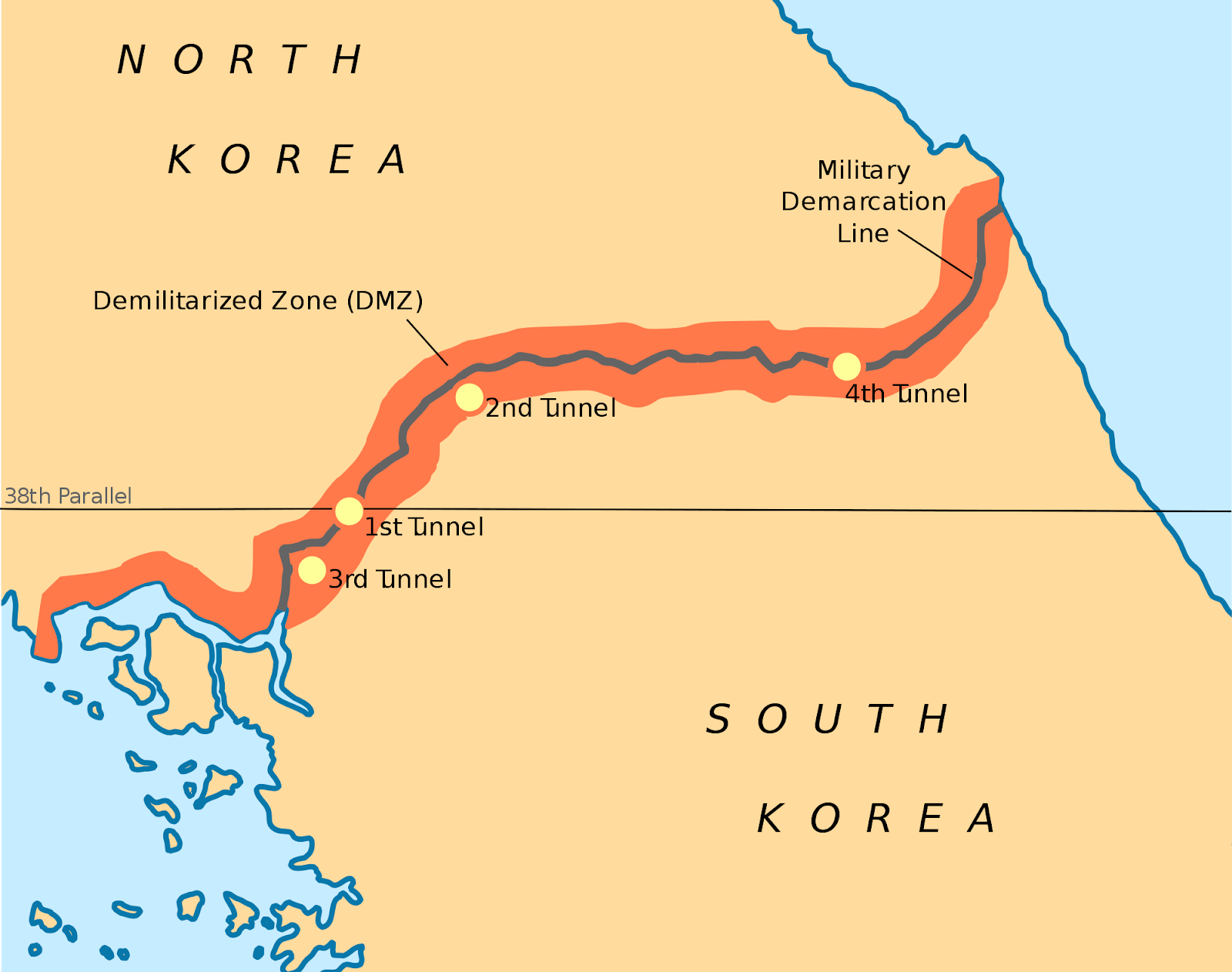

After the war, a buffer zone called the demilitarised zone (DMZ) was set up along the 38th parallel to prevent another war from taking place and to prevent people from reuniting or escaping. Since the war didn’t end officially, the US kept its bases in South Korea and there are about 23,500 personnel stationed there.

The peninsula that was once ‘one’ was now divided on ideological differences. In the years after the war, the two Koreas competed for legitimacy and international recognition abroad. DPRK and ROK continued to view each other as potential threats and propaganda against each other was rampant in the peninsula. The inter-Korean relations, however, worsened with the increasing provocations by the North. In 1968, North Korean commandos attacked the South Korean Blue House. In 1976, North Korean soldiers killed two US Army officers in the truce village of Panmunjom. Later, in 1987, two North Koreans bombed a Korean airliner carrying over 100 passengers to hinder the 1988 Olympic Games that were scheduled to be held in Seoul.

South Korea’s first democratically elected President, Roh Tae-woo launched a diplomatic initiative known as ‘Nordpolitik’, proposing the development of a ‘Korean Community’. As part of the policy, South Korea established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and China. Additionally, it led to direct inter-Korean trade and started inter-Korean sports exchanges. In 1991, both countries signed the Agreement on Reconciliation, Non-Aggression, Exchanges, and Cooperation and the Joint Declaration of the Denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula.

In 1998, the ‘Sunshine Policy’, or as it is formally known, the ‘Comprehensive Engagement Policy towards North Korea’ was announced by the then President of South Korea, Rho Moo-hyun. The policy aimed at loosening containment on North Korea, embracing North Korea, and eventually making the North Korean government denuclearise itself. The objectives of the Sunshine Policy were more specific and substantial than any of the previous policies towards North Korea.

The Sunshine Policy prompted a reduction of military tension and improved inter-Korean relations. It led to increased economic and cultural interactions between not only the leaders but also the people. These regular interactions created a sense of safety and stability in the Korean peninsula and rekindled the prospect of unification. The policy also led to the spread of South Korea’s soft power in North Korea, shaking their faith in their communist government. South Korean Choco Pies and Dramas spread like wildfire, and people started getting and consuming these illegally. Soon it started changing the way North Koreans viewed South Korea as they realised that the South wasn’t the poor, struggling country their leaders had them believe. Instead, they were the ones living in a poor, struggling country.

As a result of the policy, a breakthrough in the inter-Korean relations came at the start of the century with the first Inter-Korean Summit of 2000 as the leaders of both countries met in Pyongyang (capital of North Korea). The summit resulted in a joint peace declaration, with Kim Jong-Il and Kim Dae-Jung agreeing to promote unification and humanitarian and economic cooperation. The meeting resulted in a series of reunions of families separated by the Korean War, as well as a joint factory park in the North’s border town of Kaesong in 2004.

The policy, however, was riddled with criticism. Despite its benefits, the policy failed to change North Korea’s behaviour. Many accuse the policy not only of being ineffectual but also immoral, giving North Korea access to money to develop nuclear weapons, instead of the humanitarian purpose it was supposed to serve. Some conservatives believed that the policy weakened the US-South Korea alliance. By continuing to help the North with financial aid even after 9/11, South Korea offended the US, which had placed North Korea on its ‘Axis of Evil.’ This stopped the ROK-US relations from advancing further, thus, blocking the South Korean economy’s potential to grow during the early 2000’s.

In 2006, North Korea conducted its first nuclear test and with the worsening international sentiment towards North Korea, the South decided to hold an inter-Korean summit. This led to the second meeting in 2007 between President Roh Moo-hyun of the Republic of Korea and Kim Jong-il of the DPRK, in Pyongyang. The summit culminated in an eight-point agreement as the two leaders pledged to promote and expand joint economic, military and family reunion projects. The declaration also expressed its willingness to replace the existing armistice agreement with a permanent peace regime. But the agreement didn’t lead to concrete results as the North continued to carry out a series of nuclear and missile tests.

Lee Myung-bak’s presidency (2008-13) heralded a major change in inter-Korean relations as he decided to abandon the Sunshine policy (in 2010) and take a more hard-line stance against the North. Upon taking office, the Lee administration curtailed aid to the North. As a result of the shooting of a South Korean tourist in a restricted zone of Mt Geumgang in 2008, they ordered a suspension of tourism in the area. Inter-Korean relations continued to deteriorate in 2009, with North Korea nullifying the past inter-Korean agreements. South Korea retaliated by condemning nuclear and missile tests by the North.

The tension between the two remained high as North Korea attacked South Korea almost 20 times post the attack in 2009. Peace in the Korean Peninsula seemed impossible to reach in the following years and it was only in 2018 that the situation took a turn for the better.

As South Korean President Moon Jae-In revived the Sunshine Policy in 2017, North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un proposed to send a delegation to the upcoming Winter Olympics in South Korea in his New Year address for 2018. This olive branch led to the Seoul-Pyongyang hotline being reopened, a K-pop concert in North Korea, and propaganda no longer being broadcasted on both sides. At the Winter Olympics, North and South Korea marched together in the opening ceremony and fielded a united women’s ice hockey team.

On April 27, 2018, North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un met with South Korean President Moon Jae-In in the Demilitarised Zone at Panmunjom. It was a historical moment as this summit marked the first time a North Korean leader entered South Korean territory since the Korean War. Their discussions centred on the denuclearisation of the Korean peninsula and a peace settlement. The summit ended with both countries pledging to work towards complete denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula and to declare an official end to the Korean War within a year. Moon and Kim also pledged to reconnect east and west coast roads and railroad tracks and reopen the inter-Korean Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC).

However, many US and ROK experts are sceptical because North Korea didn’t disclose the composition and/or size of its nuclear material or warhead stocks and facilities. They also didn’t agree upon what constitutes ‘denuclearisation’, nor did they agree upon a timeline or verification measures for dismantlement.

Post the summit, North Korea adjusted its time zone to match the South’s, and South and North Korea fully restored their military communication line on the Western part of the peninsula. In November 2018, a South Korean train crossed the DMZ border with North Korea marking the first time a South Korean train entered North Korean territory since 2008.

Jenny Town, the assistant director of the US-Korea Institute at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, explained North Korea’s behaviour by saying, “Kim Jong-un is trying to repair the relations that have deteriorated over the last few years while they developed nuclear weapons.”

In August 2019, South Korea’s President, Moon Jae-In vowed to achieve the unification of the Korean peninsula by 2045, a century after the liberation of the peninsula. However, despite the proclamations and friendly summits, reunification seems a distant dream. DPRK has given a formal commitment to unification, but it likely does not want unity. Reunification would come at the cost of NK’s demise, with the North Korean elite being implicated in human rights abuses and corruption.

The cultural gap between the two countries has been widening, and a cultural shock and unrest for North Koreans would be inevitable. Like any other developed capitalist country, South Korea is fast-paced and fosters a competitive environment. South Korea is also a highly globalised country with English being used by many. North Korea, on the other hand, is a poor isolated country, where food has been scarce and praising the Supreme Leader has been abundant. North Korean defectors have historically struggled to assimilate. They usually suffer from depression and cannot find work, leading to a few of them returning to the North. On a nation-wide level, it will become more difficult to balance out these differences and to allow for assimilation of the two cultures.

Because of such differences, people don’t identify with each other despite being ’Koreans’. The older people, who’ve grown up in the peak of ‘the sunshine era’, support reunification in a more historical and humanitarian context. The younger, who grew up in the more conservative era have grown indifferent to their ‘brothers’. According to a 2017 survey conducted by the Korean Institute for National Unification, 14% of South Koreans in their 20s, and around 63% over-50, wanted reunification.

There are economic problems to consider too in this ordeal. DPRK’s GDP is less than 1% of ROK, which is the world’s 11th biggest economy. The South Korean population believes their hands are already full of domestic problems of unemployment among the youth, an ageing population, sluggish growth, and corruption scandals involving the nation’s highest office to take an additional burden of absorbing the North Korean economy too.

Finally, the nuclear program deters South Korea and American intervention. DPRK, a small, half-country, built these elite weapons for the sole purpose of standing tall against its enemies and routinely asserts that the United States pursues a ‘hostile policy’ towards it. In 2018, Kim Jong-un stated that he would abandon his nuclear weapons only if the US agreed to formally end the Korean War and promised not to invade his country.

North Korea’s marriage of convenience with China acts as another hurdle in unification. American influence has been increasing in East Asia over the past few years, with North Korea remaining the only country that hasn’t succumbed to the US yet. Unification of the Korean Peninsula would lead to a further increase in the US’ influence in the region. Until, however, China changes its threat evaluation of the US, North Korea is relatively secure.

For the North Korean commoners, however, reunification remains the only hope for access to a better life. The only other way is by risking their lives and crossing the border, thus, defecting. While the rich and elite enjoy the current state, it’s the people belonging to lower classes who want this unification, especially the youth. With the growing access to South Korean and Chinese media, they are becoming more cognizant of the opportunities that lie outside of the DPRK.

A few days ago, on May 3, 2020, North and South Korea exchanged gunfire around the South’s guard post. Despite the South Korean military believing the gunshots by North Korea to be accidental, it is still unclear if that is the case or if a bigger strategy is at play post-Kim Jong-Un’s much-awaited appearance.

Thus, a deescalation of military troops from the demilitarised line and nuclear weapons from both sides would be a prerequisite for any peace talks to take place. This, however, is just the starting point. The road to unification is long. The gap between the two sides would need to be balanced out by exposing the people to each other’s cultures and lifestyles gradually. Nevertheless, unification is becoming necessary with each passing day as North Korea continues to control the rights and lives of its people. It is important to do it sooner rather than later, for the gap between the countries will only widen, increasing the cost of unification and making the South Koreans believe it to be unnecessary.

Subscribe to The Pangean

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox